What are the characteristics of LBQ groups?

This chapter describes the basic infrastructure of LBQ organizing. It reviews when LBQ groups were founded, where they are based, the extent to which they are registered, and how they are staffed. This chapter also discusses the movements LBQ groups identify with and the strategies they use in their work.

Characteristics of LBQ groups

Regional distribution and year of founding

LBQ groups are young, quickly growing in numbers, and organizing all around the world.

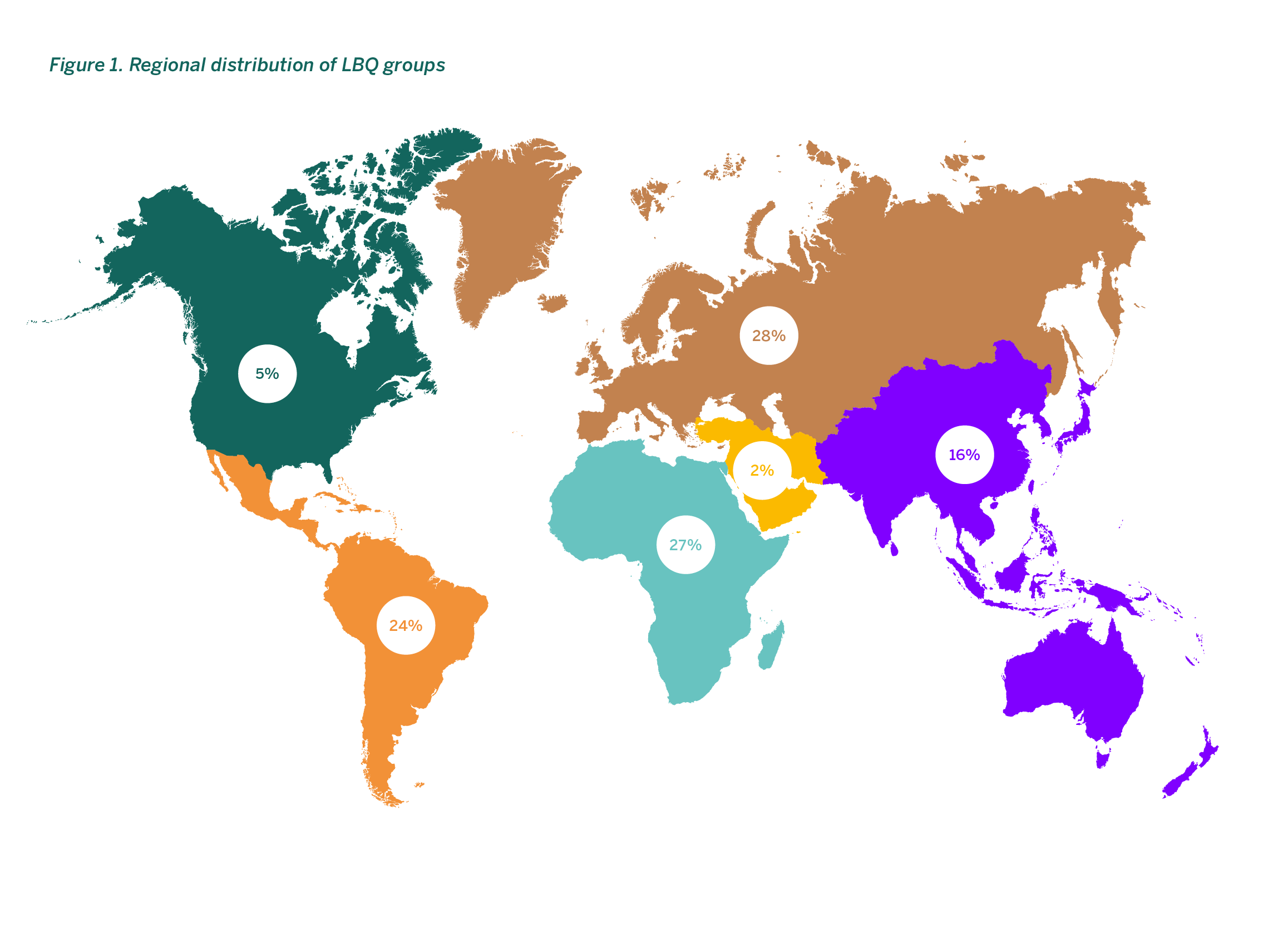

LBQ groups in our sample are organizing in all regions of the world, demonstrating a vibrant movement that is active across the globe. 39 — The small showing of LBQ groups from the Middle East/ Southwest Asia in this sample highlights a problem seen in other research (e.g., trans and intersex groups and young feminists) that aim to be globally inclusive but have difficulty obtaining data from groups in this region. This informational void on the specificities of LBQ priorities and organizing in the region invisibilizes the work of Middle Eastern LBQ activists and is most likely an important factor in how underfunded the region is.

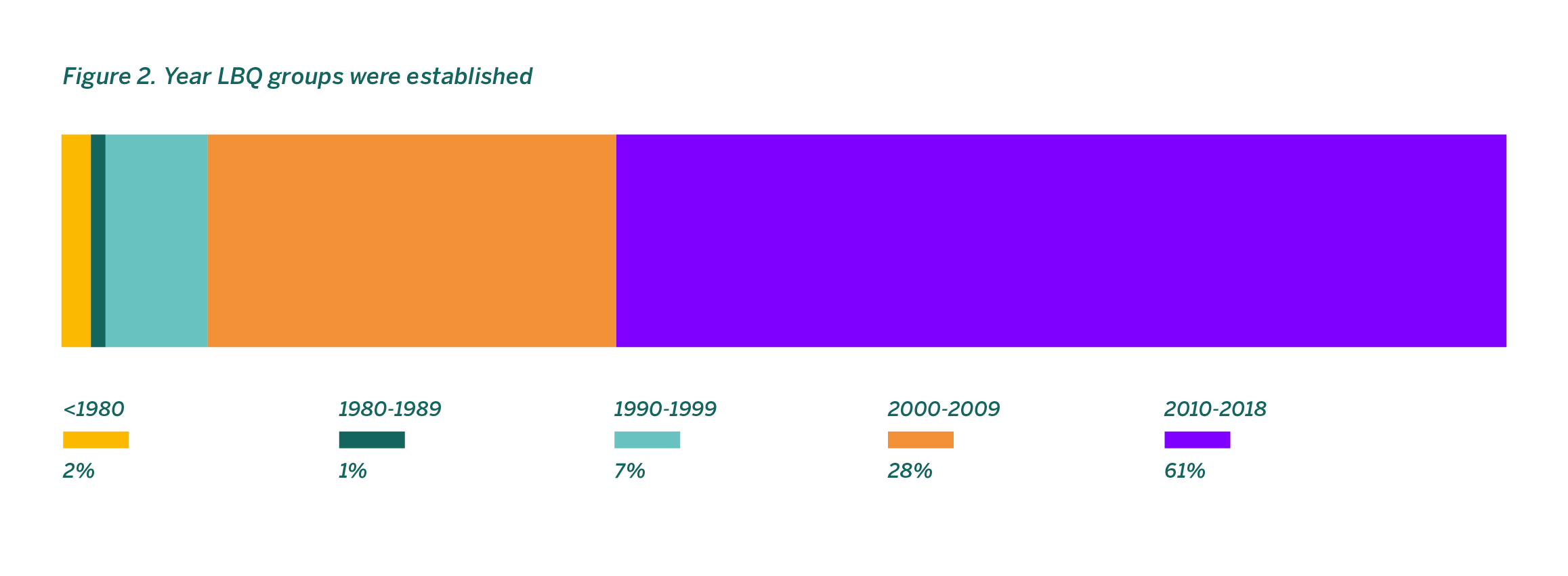

It is also an actively growing movement. Although groups responding to the survey were founded as long ago as 1968, most groups (89%) have been founded in the last twenty years, with 61% established since 2010, highlighting the tremendous growth of LBQ groups in the last two decades. This trend holds true across all regions, with the exception of groups in North America whose founding dates are more evenly distributed over the last 30 years.

Registration status

The majority of LBQ groups are registered; however, there are significant differences across regions.

Globally, more than half (60%) of LBQ groups are registered, 9% are in the process of registering, and 31% are not registered. Across regions, however, registration varies noticeably. In North America, where 80% of LBQ groups report being registered, the most of any region in our sample, minimal legal impediments likely make it easier for groups to register. 40 — Daly, F DrPH, (2018). The Global State of LGBTIQ Organising: The Right to Register. New York: OutRight Action International. At 50%, registration of LBQ groups is lowest in Asia and the Pacific. Many factors may contribute to this, including complex registration processes, costs of registration, and local political contexts, to name a few.

Homophobic and transphobic bias in regulatory frameworks is an important factor in how many LBQ groups are registered. A recent study on the right to register shows that in 55 countries, LGBTQI organizations cannot legally register as LGBTQI organizations. It found that, for example, in Africa, where 70% of LBQ groups in our sample report being registered, 39% of LGBTQI groups either use neutral language in describing the objectives of their group when registering or register on the basis of focusing on other issues (e.g. women’s rights or health rights). 41 — Ibid. Pg 20-21

Lack of registration can act as a barrier to accessing funding from foreign and domestic foundations and government sources, and impede public confidence, collaboration with other civil society organizations, and relationships with government officials, contributing to LBQ groups’ concerns about organizational sustainability. Indeed, LBQ groups with larger budgets are more frequently registered, suggesting that registration provides opportunities for groups to access funding. For example, 86% of LBQ groups with medium budgets and 88% of LBQ groups with large budgets are registered, while only 34% of zero budget and 52% of small budget groups report being registered.

Movements and issues

LBQ groups are working intersectionally.

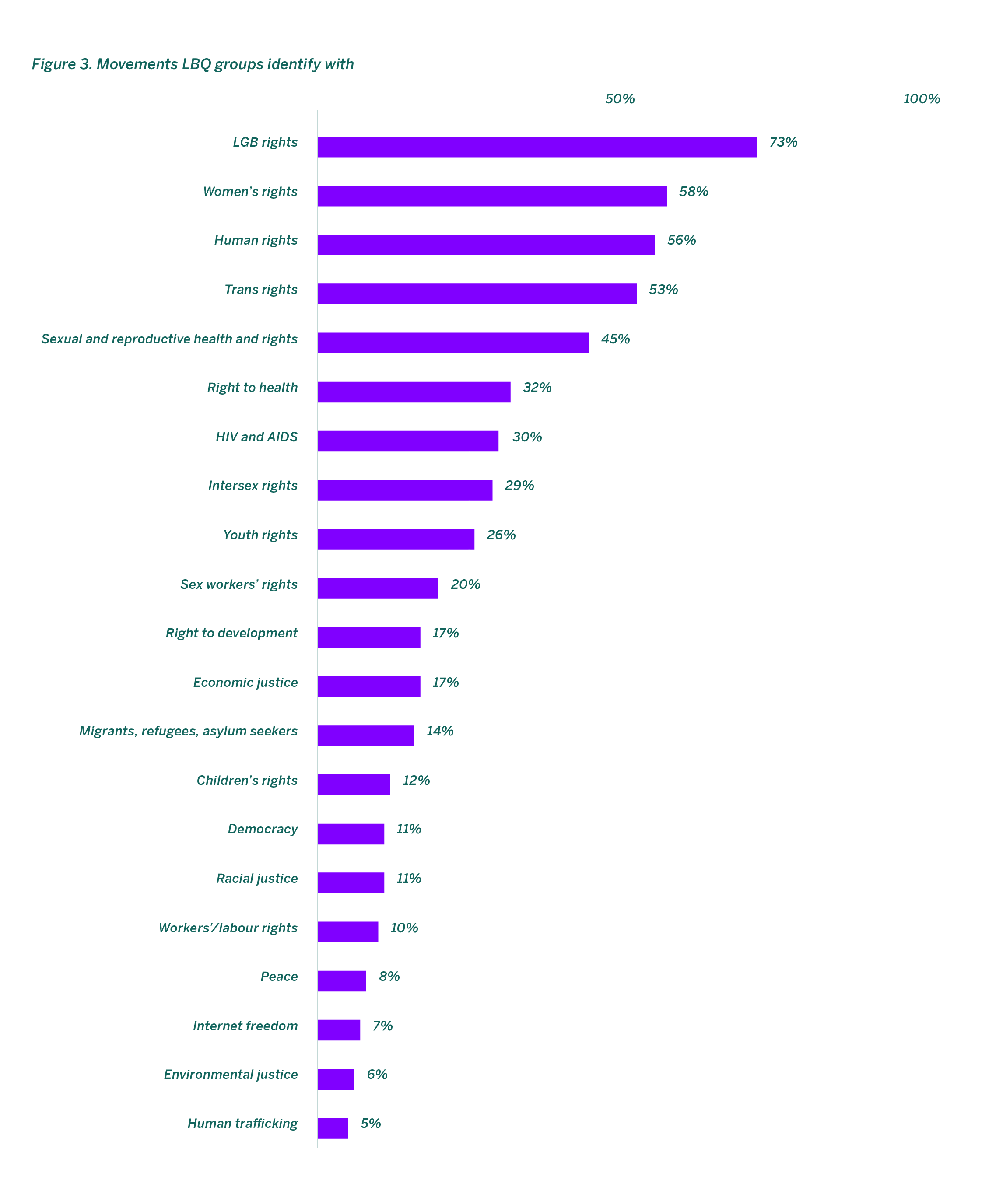

LBQ groups are working intersectionally and choosing not to be constrained by artificial issue “silos” that can limit work across movements and issues. More than half of LBQ groups identify with lesbian, gay, bisexual, and trans movements and women’s rights movements because their lives sit at the intersection of both. They also identify with broader movements and issues such as sexual and reproductive health and rights (45%), the right to health (32%), HIV and AIDS (30%), rights of intersex people (29%), young people’s rights (26%), and sex workers’ rights (20%), among others.

The broad nature of work being done by LBQ activists underscores how LBQ activists prioritize intersectional approaches in their work and tie their communities’ well-being to a range of social justice and human rights issues. In doing so, they make visible the needs of LBQ communities across different issue areas and also contribute to progress in other movements.

Activists’ strategies

Multiple strategies are at the heart of LBQ organizing.

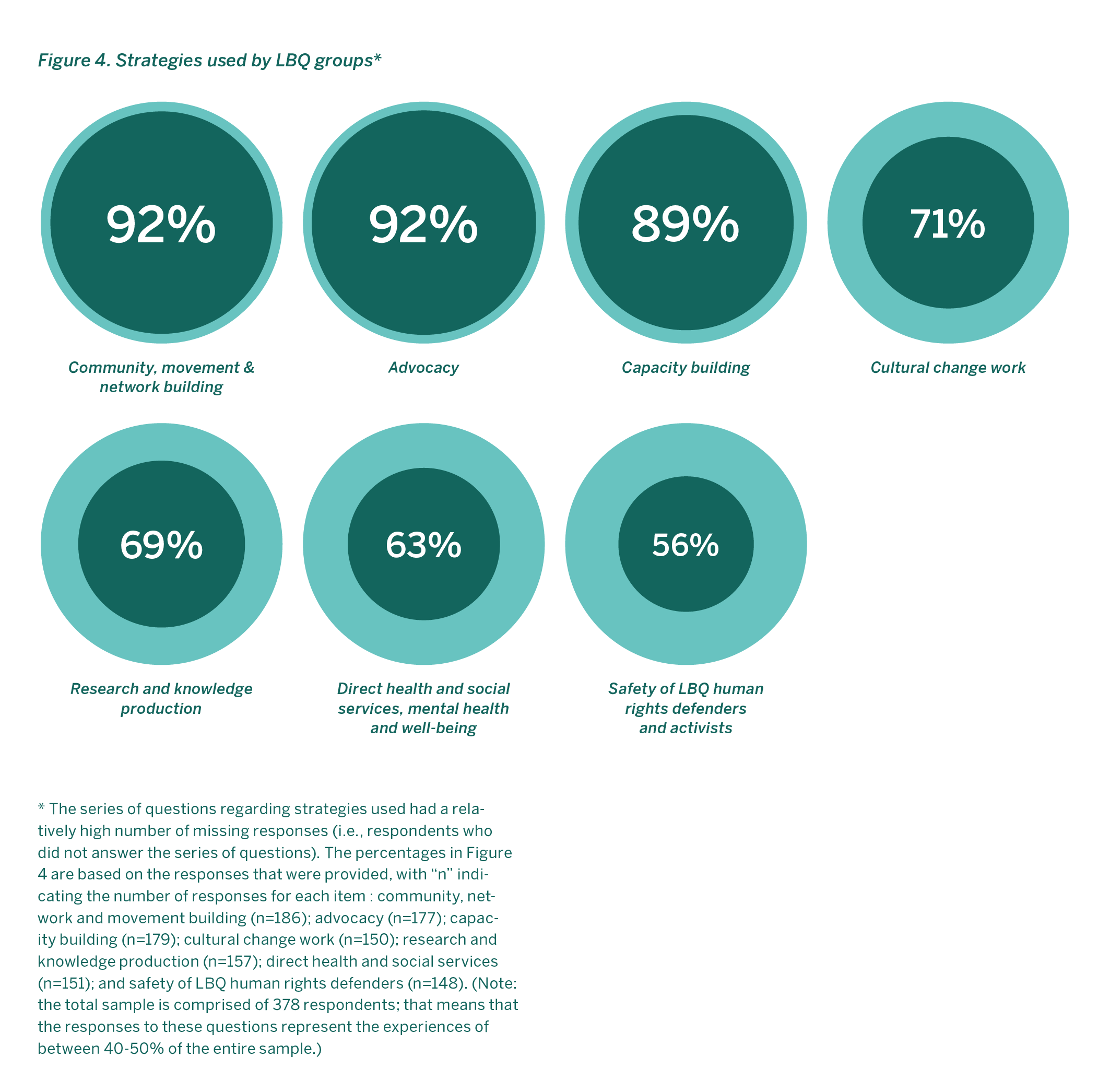

LBQ groups are using wide-ranging strategies in their work, and even among groups using the same strategy, diverse sub-strategies are being deployed. 42 — Respondents could select all the strategies that they use in their work. Movement building, advocacy, and capacity building were the most common strategies used by LBQ groups. Of the groups doing advocacy, most (85%) worked primarily at the national and local levels, but more than a third (39%) also worked regionally and internationally. Among those engaged in capacity building, groups equally prioritized internal-facing priorities, such as strengthening LBQ communities (74%), and the external work of building knowledge about LBQ communities and issues (73%).

Cultural change strategies are also essential to LBQ organizing. Groups are harnessing the power of creativity to counter the invisibility of LBQ people and issues, and address the restrictive social norms that underpin the oppressions that LBQ people face. Among the groups that reported using cultural change strategies in their work, more than half created media (58%) and used art for their activism (53%), while over a third (37%) preserved the rich history of LBQ organizing through community archiving. Other strategies that are essential to increasing the visibility of LBQ people and issues are also an important part of LBQ organizing. More than two-thirds (69%) of groups engaged in research and knowledge production, of which the majority (63%) specifically focused on building knowledge about human rights violations experienced by LBQ communities.

LBQ groups are also providing services that are critical to the safety and well-being of LBQ communities, oftentimes filling service gaps by providing culturally competent services to their own communities. More than half (56%) of groups used safety-related strategies in their work; of these, more than three-quarters (84%) focused on training LBQ human rights defenders and activists on physical and digital security measures, while more than half (54%) were providing LBQ people with emergency support, such as safe houses and relocation support.

Service provision by LBQ groups is significant. Of the 63% of groups engaged in service provision, 66% offered mental health and wellness services for LBQ communities and 63% provided direct health and social services. The prevalence of these types of strategies emphasizes the hostile circumstances under which LBQ activists work, the life-saving support LBQ groups are offering to their communities, and the priority placed on addressing trauma experienced by LBQ communities and ensuring physical and mental well-being.

Staff and volunteers

The majority of LBQ groups are understaffed and rely heavily on volunteers.

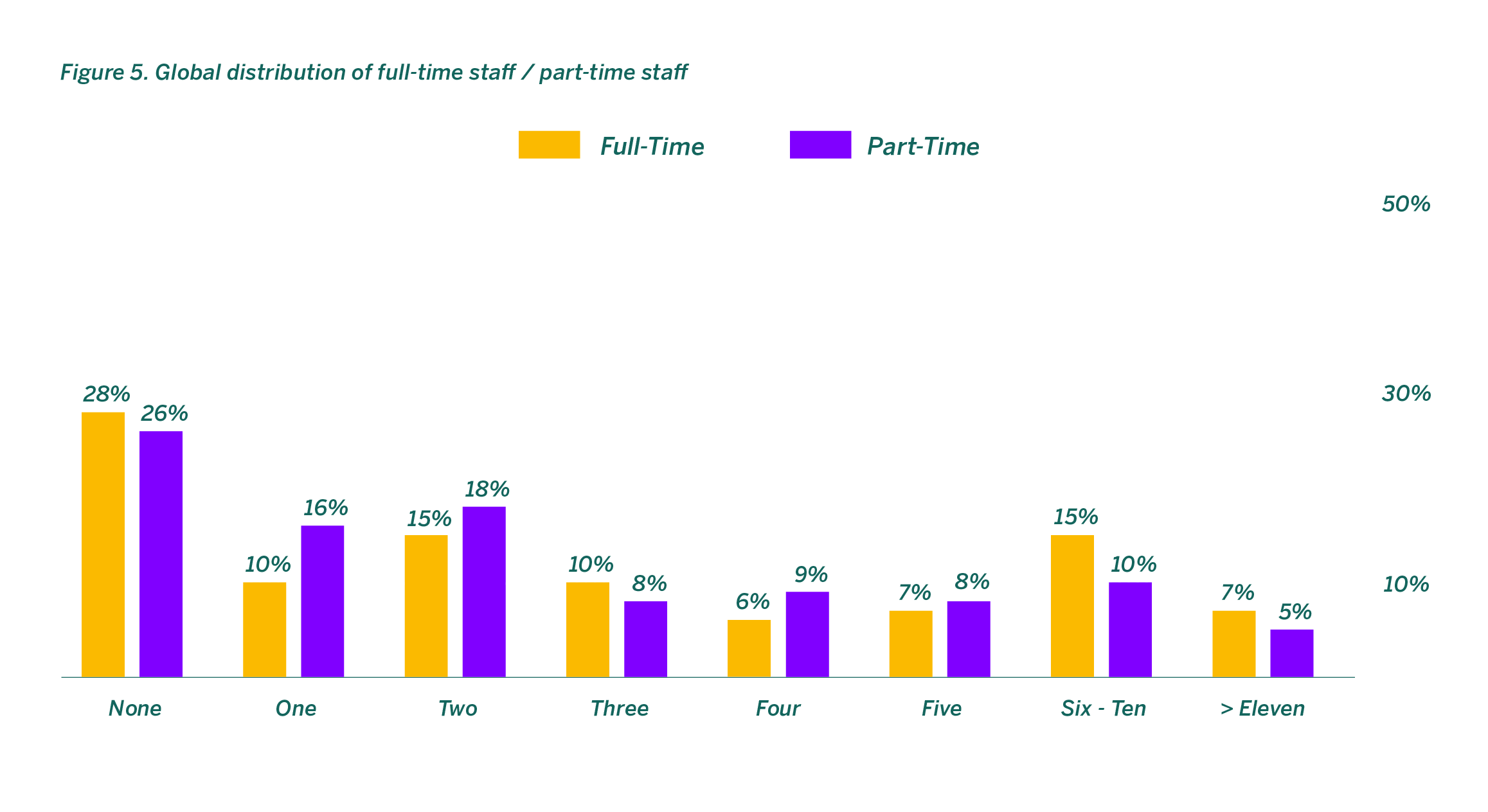

A lack of paid staff can be one of the biggest obstacles to executing a group’s vision. LBQ groups have a median of two full-time staff and two part-time staff. Twenty-eight percent of groups have no full-time staff, and a quarter (25%) report having only one or two full-time staff members. Part-time staffing is equally bleak. A quarter (26%) of LBQ groups have no part-time staff members while a third (34%) have only one or two. The experience of LBQ groups in our sample highlights that LBQ groups are doing their work with the support of very few paid staff, if any.

Even among groups with a higher number of staff, the actual experience of staffing can vary. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the staff of many LBQ groups are underpaid. Funding shortages have led activists to share salaries (i.e., distribute one salary among multiple staff members), accept a stipend as a salary, or donate their salaries back to their groups in order to implement activities that remain unfunded. Groups have also noted that secondary employment is sometimes necessary in order to subsidize their work and activism. 43 — Throughout this research, consultations with LBQ activists and groups have frequently returned to the staffing practices dis- cussed here. To supplement the research findings, anecdotal evi- dence drawn from the case studies and input from the activist advisory committee was used to highlight the experiences of LBQ groups as related to staffing.

LBQ groups are powered by volunteers. Ninety percent of LBQ groups engage volunteers to support their work, with a median number of five volunteers. This is consistent among LBQ groups regardless of region or budget size. This may indicate that LBQ groups are strongly rooted in their communities and have a strong organizing model or vibrant base of constituents. The high number of volunteers and low levels of staff, however, also suggest that volunteers are filling gaps in paid staff. Sustainable staffing of LBQ groups is necessary to reduce activist burnout and strengthen LBQ movements.

The questions regarding full-time staff were answered by n=278; part-time staff, n=273; and, volunteers, n=316.

Case Study

Aireana

Paraguay

Lesbian feminists in action: Creating spaces to change culture

As in many Latin American countries, lesbians in Paraguay are not criminalized, but neither are they legally protected. Existing in this vacuum has negative implications for those that need protection — for instance, lesbian mothers or binational couples — and especially for those that are more vulnerable to discrimination in the workplace or to attacks in public or private spaces because of their ethnicity, class, age, gender expression, and other factors. Pentecostal churches, which actively campaign against sexual rights, have increased their power and influence in Paraguay. Against this backdrop, Aireana Grupo por los Derechos de las Lesbianas was established as a lesbian feminist group in 2003.

Read more ▾

Initially part of an umbrella gay and lesbian group, Aireana’s founding members realized the agenda was set by the men, leaving little space for their issues as lesbians; so they created their own group. Aireana is concerned not just with lesbian liberation or the ‘LBQ collective’, but with the liberation of all oppressed peoples, including trans people, other sexual and gender dissidents, cis-straight women, and all those who are economically and racially oppressed. Their intersectional approach is embodied in the visible presence of their drums band which performs in other movements’ demonstrations, such as those led by peasants or by the families of victims of institutional violence and in their leadership of a multi-stakeholder coalition, including people with disabilities, Indigenous and rural peoples, and migrants, among others, that led to the Anti-Discrimination Bill in Paraguay.

Aireana works at many different levels ranging from political advocacy (nationally and regionally) to running a hotline. However, they view their cultural change work — projects like their theatre group or drums band — as having the greatest and most lasting impact.

Their view of liberation also translates into autonomy in their activism, organizing, and advocacy. For example, they are selective about what funding they accept (e.g., from feminist funders or foundations whose resources do not come from sources that Aireana would find politically objectionable).

In 2005, Aireana opened La Serafina, a lesbian-feminist cultural space that is open to all people. Encountering hostility in public is a daily experience for sexual and gender dissidents, feminists, leftists, and other progressive people, and La Serafina offers a space that feels free and safe. It has also been effective in making people more open and accepting towards sexual and gender diversity through enjoying the space together. While the space has never made a profit, Aireana values the freedom it offers in a hostile context. Someone told them once that, at peak time, La Serafina looked like one of the “Sense8 44 — “Sense8” is a Netflix television series that has been recognized for its portrayal of LGBTQ characters and diverse sexualities and sexual expression. orgies”, and they feel very proud of that.

“Life is to be enjoyed. We don’t want Aireana ever to be a chore, a burden for us, but rather something that we – and others – can enjoy. And nurturing creativity in us and in others is the best way we have found to do that.”

Since 2005, Aireana has hosted an annual LesBiGayTrans Film Festival, drawing an increasingly large audience each year. Aireana has found that film provides a good entry point for people who have limited access to discourses about sexual diversity, for example, teachers bringing entire high school classes to attend events, and inviting Aireana members to join discussions afterwards.

Another important cultural project is the Tatucada, Aireana’s drums band which is open to interested cis or trans women or non-binary people. Tatucada is well-known in social justice demonstrations in Asunción, from environmental justice to Indigenous rights, or in support of justice for victims of Paraguay’s long military dictatorship. It has allowed Aireana to have a fluid relationship with other social movements and to open up dialogues with them. Tatucada allows its members to experience rhythms and become a ‘force of nature’ while playing, and this is valued highly by Aireana. The name Tatu means armadillo in Guarani, and it is also used to refer to the vulva (the reason it was chosen).